Historic Canadian Flags & Banners

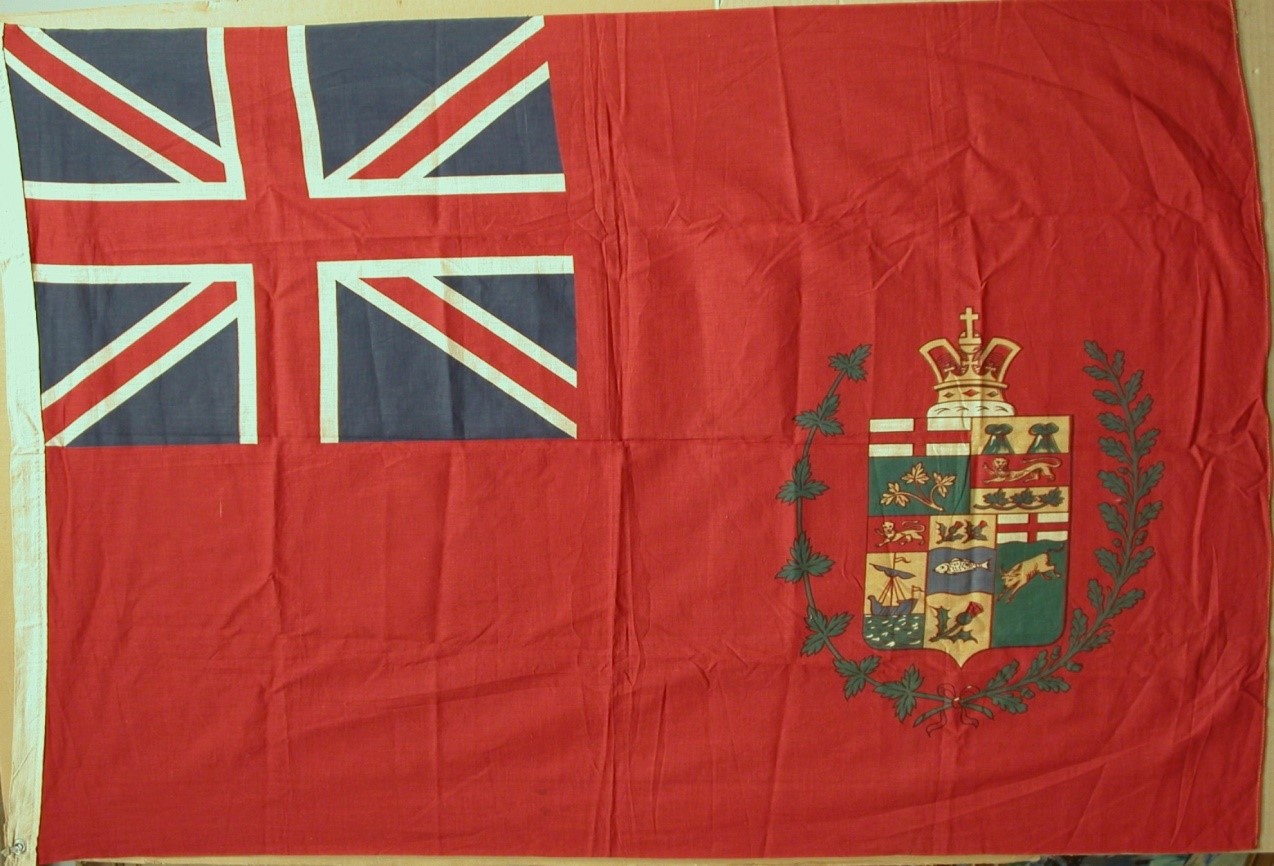

1. Canadian Red Ensign Flag with Five-part Coat of Arms. 21 ¼ x 35 inches. colour printed cloth. [1870 or thereafter]. $950

This flag contains the combined coat of arms of the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Manitoba, topped by a stylized Saint Edward’s crown, surrounded by a wreath of maple and oak leaves. These particular arms were in use from the time Manitoba joined confederation in 1870 (previous flags continued to be used for years thereafter even though the arms may have changed in the meantime). As each province or territory joined Canada, its arms were incorporated into the Greater Arms of Canada and thus added to the flag. Variations of the arms continued to appear on flags until 1921.

2. Canadian Red Ensign Flag with Seven-part Coat of Arms. 69 x 138 inches (5’ 9 x 11’ 6 inches). red, white, and blue sewn cloth, with applied screen-printed medallion of white cloth, featuring the combined coats of arms of the seven provinces of Canada (Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Manitoba, British Columbia and Prince Edwards Island) surrounded by a wreath of maple and oak leaves with a beaver, all topped by the crown (condition of cloth is slightly worn and toned, with small holes and darning repairs). [possibly produced in Canada, or in Britain for the Canadian market 1873-1892]. $1,500

The unusually large scale of this flag, 5.9 x 11.6 feet, would indicate it was previously uses on a very high flag pole, a government building, or tower. For example, according to the “Public Works and Government Services Canada” website, flags that are flown over the Peace Tower are 7.5 x 15 feet, and flags flown over the East or West Blocks are 4.5 x 9 feet in scale.

"...The "official" red ensign approved by Parliament in 1868 incorporated a shield featuring elements from the Coats of Arms of the four original Provinces in Confederation - Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. That version was never officially changed until the red ensign featuring the shield from Canada's new national Coat of Arms was adopted in 1922. However, as new Provinces entered Confederation, flag-makers took it upon themselves to add elements from their Coats of Arms to the shield on the ensign. Most commonly, these ensigns featured what Canadian flag historian Dr. Alistair Fraser has referred to as a "dog's breakfast" of Canadian symbols with the shield surmounted by a crown, and surrounded by a wreath with a beaver at the bottom, the whole emblem often appearing on a white background centered on the red fly. By 1873, Manitoba, British Columbia and Prince Edward Island had joined Confederation, and a seven-province shield became the norm until after 1905 when Alberta and Saskatchewan were created. It should be noted that some of the Provinces had rather different Coats of Arms back then, and B.C. adopted a new Coat of Arms more like its present design in 1892 or thereabouts. These "unofficial" flags were very popular, and were commonly flown everywhere ... including on many Government buildings!" (“Victorian Wars Forum, British Military Campaigns from 1837-1902” website)

3. Canadian Red Ensign Flag with Seven-part Coat of Arms. 15 ½ x 28 inches. colour printed cloth (screened on one side only), featuring a white medallion with the combined coats of arms of the seven provinces of Canada (Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Manitoba, British Columbia and Prince Edwards Island) surrounded by a wreath of maple and oak leaves with a beaver, all topped by the crown. framed. [possibly produced in Canada, or in Britain for the Canadian market, 1873-1892]. $900

4. Canadian Red Ensign Flag with Nine-part Coat of Arms. 36 x 52 inches. colour printed cloth. [circa 1905-1921]. $800

A flag with a nine-part coat of arms was in use from 1905 when Alberta and Saskatchewan were created. Though technically an unofficial Canadian Flag, these examples were probably used by the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War. Similar examples were also known to have been used by Canadian Church congregations. Though the Canadian Red Ensign was flown by Canada’s merchant ships, the flag remained unofficial on land. This situation led to many variations of the flag’s design. In 1921 the Canadian government petitioned King George V to provide a national coat-of-arms for Canada and it was these new arms that were subsequently used in the Canadian Red Ensign flag until 1965.

5. 1921 Canadian Red Ensign Flag with Royal Arms of Canada. 19 x 38 inches. colour silkscreened and stitched linen cloth, cotton mast, with jute rope and wooden dowel (some moth depredations). bearing label: “Made by Grant Holden Graham, Ottawa”, [c1922-1957]. $300

6. 1921 Canadian Red Ensign Flag with Royal Arms of Canada. 52 x 216 inches. colour silkscreened and stitched linen cloth, cotton mast, with jute rope and wooden dowel. bearing tag inscribed “MSN”. [c1922-1957]. $1,000

“In 1922, the unofficial version of the Canadian Red Ensign was changed by an Order in Council and the composite shield was replaced with the shield from the royal arms of Canada, more commonly known as the Canadian Coat of Arms. Two years later, this new version was approved for use on Canadian government buildings abroad. A similar order in 1945 authorized its use on federal buildings within Canada until a new national flag was adopted”. In 1957 the ensign was again changed when the coat of arms was modified to include red maple leaves (instead of the previous green) and the harp in the coat of arms for Ireland was simplified. (“First Canadian Flags” Canadian Heritage, website)

7. 1965 Canadian Maple Leaf Flag. 27 x 56 inches. red and white stitched nylon cloth. $300

“The search for a new Canadian flag started in 1925, when a committee of the Privy Council began to research possible designs. However, the committee never completed its work. A parliamentary committee was given a similar mandate in 1946, but Parliament was never called upon to formally vote on the more than 2,600 designs received. Early in 1964, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson informed the House of Commons that the Government wished to adopt a distinctive national flag. As a result, a Senate and House of Commons Committee was formed and submissions were called for once again.” After a rather emotional and at times contentious “National Flag Debate”, a design was finally approved and the official ceremony inaugurating the new Canadian flag was held on Parliament Hill on February 15, 1965. (History of the National Flag of Canada, Government of Canada website)

8. Victory Loan Honour Flag, Second Campaign. 48 x 101 inches. stitched red and white cotton cloth, with silkscreened blue Maple Leaf, and attached jute hanging rope. [Ottawa: Second Victory Loan Campaign, 1918]. $800

Flag for the Second Victory Loan Campaign of 1918. Communities (cities, towns, districts) who made their full bond sales quota received the flag and businesses were presented with a banner. Originally called “Victory Bonds” after 1917, the name was changed to “Victory Loan”. The Second and Third Victory Loans were floated in 1918 and 1919 and altogether raised $1.34 billion for the war effort and reconstruction. A fairly extensive drive was conducted in Toronto in 1918. (Ottawa, Library and Archives of Canada, website; Toronto, “Canadian Posters from the First World War” Archives of Ontario, website; Norman Hillmer, The Canadian Encyclopedia, online; Alistair B. Fraser, “The Flags of Canada”; “Victory Bonds”, Archives of Ontario, Toronto; Jamie Bradburn “Buy Victory Bonds”)

9. *100% Victory Loan 1919 (Honour Emblem). 44 x 30 ½ inches. hanging banner. colour silkscreened cotton cloth with wood lattice hanging bar (broken) and metal ringlets (only 2 of three remaining). some creases and damp-staining, frayed edges to the right side (picture does not show the full banner, as there is another five inches folded over the top). [Ottawa: Third Victory Loan Campaign], 1919. $1,000

The “Honour Emblem” for the third victory loan campaign of 1919. According to the wording on the poster used to promote the drive “Awarded to the commercial and industrial establishments which attain the 100% standard in the Victory Loan 1919”. Communities who made their full sales quota received the flag and businesses were presented with the banner. Originally called “Victory Bonds” after 1917 the name was changed to “Victory Loan”. The Second and Third Victory Loans were floated in 1918 and 1919 and altogether raised $1.34 billion for the war effort and reconstruction.

The coat of arms of HRH Prince Edward of Wales (later Edward VIII) were used on this banner. His arms were used on this banner and on the official Victory Loan flag. In September 1919 the Prince of Wales came to Canada on a Royal visit and raised the flag in Ottawa to highlight the start of the loan campaign. The use of these particular arms is unusual as the arms include the escutcheon for Saxony (added to the arms by Edward VII because his father was a member of the house of Saxe-Coburg, Gotha). These arms were finally dropped from the Royal achievement in 1917 after George V removed all foreign titles and designations and changed the family name to Windsor. Their use on this particular occasion may have been through oversight or perhaps differences in proclaiming the Canadian usage. (Ottawa, Library and Archives of Canada, website; Toronto, “Canadian Posters from the First World War” Archives of Ontario, website; Norman Hillmer, The Canadian Encyclopedia, online; Alistair B. Fraser, “The Flags of Canada”; “Victory Bonds”, Archives of Ontario, Toronto; Jamie Bradburn “Buy Victory Bonds”)

10. The British Empire Exhibition Flag, Wembley, England. 17 x 31 inches. framed. colour silkscreened cotton, featuring the Saint George’s Cross, with the Union Flag in the upper left canton, the Arms of South Africa, Canada, Australia, and the emblem of the Great Star of India. framed. Wembley, England: British Empire Exhibition, 1924. $1,200

“The British Empire Exhibition held in 1924 and 1925 presented a chance for Canada to assert a national identity and a prominent place, as a self-governing, “white” dominion, within the British imperial family of nations. Those responsible for the government pavilion consciously sought to understate regional differences and to construct and project a unified, homogeneous image of the nation, despite its vast geographic distances and obvious differences of language and race. While their intentions were to attract investment and improve export markets for Canadian goods, the exhibition commissioners assembled a set of images intended to sum up the idea of Canada. The resulting national representation proved to be contested, fragmented, and sometimes controversial. But for Canadians who visited the exhibit, the pavilion seemed to speak on an emotional level, inspiring national identification and pride”. (Glendinning “Exhibiting a Nation: Canada at the British Empire Exhibition, 1924-1925)

“The British Empire Exhibition was opened on St George’s Day, 23 April 1924, by King Edward V and Queen Mary at the Empire Stadium...The organizers pursued four main objectives with the exhibition. They wanted: to alert the public to the fact that in the exploitation of raw materials of the Empire, new sources of wealth could be produced; to foster inter-imperial trade; to open new world markets for Dominion and British products; and to foster interaction between the different cultures and people of the Empire by juxtaposing Britain’s industrial prowess with the diverse products of the Dominions and colonies. The location for the exhibition was Wembley Park as it was regarded as one of the most easily accessible areas of London, both from the suburbs and from the rest of the country, with two mainline stations and a new station inside the exhibition grounds. A vast infrastructure project was also proposed, leading to the widening of approach roads from central London to the exhibition. The exhibition covered an area of more than 216 acres and in the two years it was open attracted over twenty million visitors. The exhibition was open for six months in 1924 and reopened in 1925 and showcased produce and manufactured goods, arts and crafts as well as historical artefacts from each of the Dominions, the Indian Empire as well as Britain’s African and Caribbean Colonies. The exhibition was also accompanied by a cultural programme and a series of conferences. Britain focused on its textiles, chemicals and engineering and was keen to emphasis its central role in ensuring progress for the whole of the Empire…” (“The 1924 Empire Exhibition” The Open University, website)